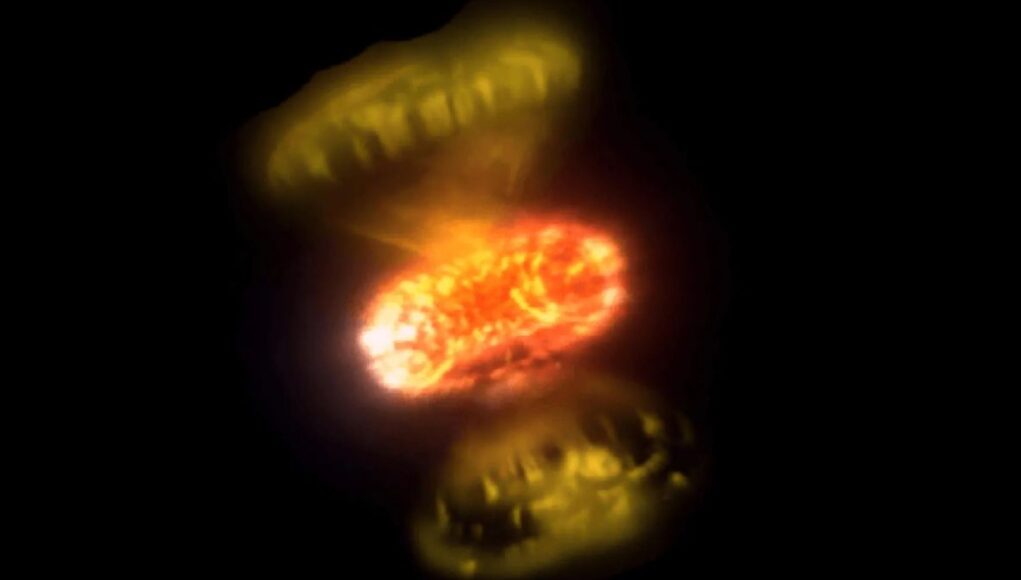

The Center for High Angular Resolution Astronomy (CHARA Array) at Georgia State University has generated detailed images of the early stages of two nova explosions that were detected in 2021. Through near-infrared interferometry, a process that combines light from multiple telescopes, the CHARA Array was able to capture in high resolution the rapidly changing conditions of their early post-explosion phase.

A nova is an astronomical phenomenon that occurs in a binary system when a white dwarf strips its companion star of hydrogen-rich gas, causing a thermonuclear runaway reaction on the white dwarf’s surface. The name derives from the sudden brightening that makes it appear as though a new star has appeared in the night sky. However, the ejecta immediately following the explosion are small and a challenge to observe, and until now astronomers could only infer the early stages through indirect methods.

“The images give us a close-up view of how material is ejected away from the star during the explosion,” explains Gail Schaefer, CHARA Array director. “Catching these transient events requires flexibility to adapt our night-time schedule as new targets of opportunity are discovered.”

Explosive Results

Schaeffer and her team observed V1674 Herculis, a nova in the Hercules constellation, and V1405 Cassiopeiae, a nova in Cassiopeia. V1674 was one of the fastest novas ever recorded, reaching its peak brightness less than 16 hours after its discovery and rapidly fading in just a few days. By contrast, V1405 took 53 days to reach its peak brightness and remained bright for about 200 days.

The image of V1674, captured just a few days after its discovery, shows an explosion that is clearly not spherical; there are two ejecta flows, one to the northwest and the other to the southeast with an elliptical structure radiating almost perpendicular to them. This is direct evidence that the explosion involved multiple ejecta interacting with each other.

Spectroscopic observations also detected different velocity components in the Balmer series of hydrogen atoms. While the absorption line before the peak was about 3,800 km/s, the component that appeared after the peak reached about 5,500 km/s.

The timing is significant. The new ejecta flow appeared in the image concurrent with the detection of high-energy gamma rays by NASA’s Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope. The collision of the different velocity streams formed a powerful, gamma-ray emitting shock wave.

The results of V1405 were even more startling. The first two observations during the peak period showed only a bright central light source and few surrounding ejections. The diameter of the central region was approximately 0.99 milliarcseconds, which when converted to distance corresponds to a radius of approximately 0.85 au (au stands for the astronomical unit, the distance between Earth and the sun).